Stine Marie Jacobsen, Teobaldo Lagos Preller "Law Shifters — Quantum No"

Participatory art project, 2015 — present

— What is "Law Shifters" and how does your project relate to the theme of dictatorship?

Stine Marie Jacobsen: "Law Shifters" is a project I've been working on for more than 10 years, since around 2015. It invites people from all over the world to imagine draft laws. The result of this project can be anything from street posters to animations, cartoons with children, plays and so on. We start by inviting people to a workshop to relitigate a real court case. I like to see how the public rules on something that has already been given a ruling by legal experts.

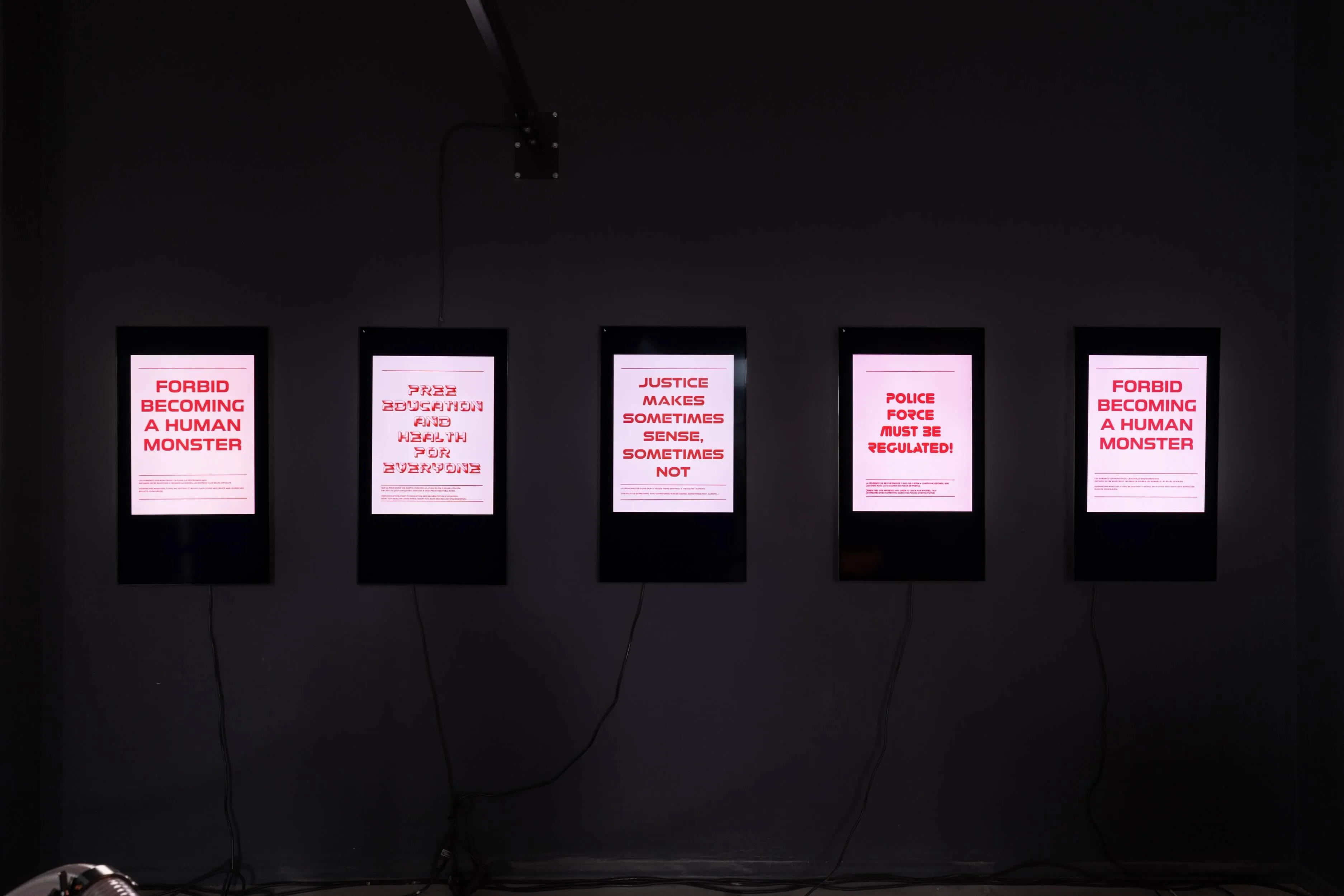

Towards the end of the workshop, the participants are sort of warmed up — and they start to imagine how we should legally regulate a certain kind of behaviour. That’s where the machine comes in. In Kreuzberg, we put a pneumatic machine on display. People are then invited to write a proposal for a law relating to freedom of speech in Germany. The proposal is then sucked up by the machine and a screen displays a translation of their proposal into legal language.

One of the best experiences we had in this project was when we were working with young teenagers from South London. These kids were predominantly Black and wanted to work on issues related to racial profiling and police brutality. So they came up with three pieces of legislation that we were able to use to lobby two politicians: one on the right to compensation in case of physical injury during a police search, another on the right to record one’s own arrest, and lastly one on the requirement of the police to take a person to the police station if they refuse to be searched in public.

These three draft laws seem so reasonable that you might think they already exist on the books. But no, actually, they do not. The children ended up meeting with these two politicians privately and influencing them in the process.

This is not an antagonistic project. It is a political educational project, which I think is a gift to legislators and politicians who need to know what people feel and perceive. Who is supposed to define what constitutes a need? Isn’t it the actual person in need? Some people would say that it’s a naive way of thinking, but I don’t think it’s naive at all.

Teobaldo Lagos Preller: We focused our thinking on the word "no" as both a negation of reality and a very primordial principle of rejection and resistance. It's one of the first words we learn. Our first reaction when we are small children is to say "no".

On opening day, the public will be able to see draft proposals from Chile that have been turned into political posters. We will focus on using material that we gathered from different workshops in Chile.

There was a point in Chile, during the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, when the word 'no' became something people relied on. In the early 1980s, the bodies of civilians who had resisted the 1973 coup were being found in the Mapocho River on a daily basis. In 1983, the group CADA (Collective of Art Actions) unfurled a banner on the Pionono Bridge with the word "no," a plus sign and a picture of a gun.

It became a ubiquitous slogan — in graffiti, advertisements, on television, and finally as the official symbol of a referendum calling on the people to approve or reject Pinochet's presence for another eight years. So we were very interested in this idea of rejection and what it means when we reject, even when we might not know what comes after that rejection.

Stine Marie Jacobsen

Stine Marie Jacobsen is a conceptual artist who practices participatory art. Jacobsen does not create self-contained 'works' but rather directs situations. Most of her projects are games, instructions, manuals, and training modules that help participants explore society and their own role in it.

Particularly important in her practice are educational programmes that the artist develops in collaboration with teachers, lawyers, researchers, and other experts.

In 2012, for example, Jacobsen launched the long-term project 'Direct Approach,' in which she invited schoolchildren to describe and analyse a particularly violent scene from a film — and then reshoot it, playing the aggressor, victim or witness of their choice. And in 2018, she ran the ‘Pidgin Tongue’ programme, in which children from Riga, a bilingual city, created a new language dictionary based on Latvian and Russian.

Stine Marie Jacobsen was born in 1977 in Denmark. She studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and at the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles. The artist has had solo exhibitions in London, Berlin, Copenhagen and Galway, Ireland. Jacobsen has participated in many international biennials, including Manifesta 2020. She lives and works in Berlin and Copenhagen.

Teobaldo Lagos Preller is a curator and art researcher. His doctoral thesis focused on the relationship between art and society in Berlin after the city's reunification. His other research interests include Latin America. In 2021, Preller co-curated the ‘Museum of Democracy’ exhibition at the Berlin gallery Neue Gesellschaft für Kunst, which explored democracy as a vanished phenomenon, like an extinct animal or a bygone culture, using examples from Latin American history.

Preller has curated several of Stine Marie Jacobsen's projects, including ‘Law Shifters’ in Chile in 2023 and 2024. In this outreach-style program, participants conceive and formulate new laws. ‘Law Shifters’ has taken place in several countries, but is particularly relevant to Chile, as much of the country's legislation is a legacy of Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship.

Teobaldo Lagos Preller was born in Chile in 1978. He studied Communication Sciences at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City, Latin American Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin, and History and Theory of Contemporary Art at the University of Barcelona. He lives and works in Berlin.