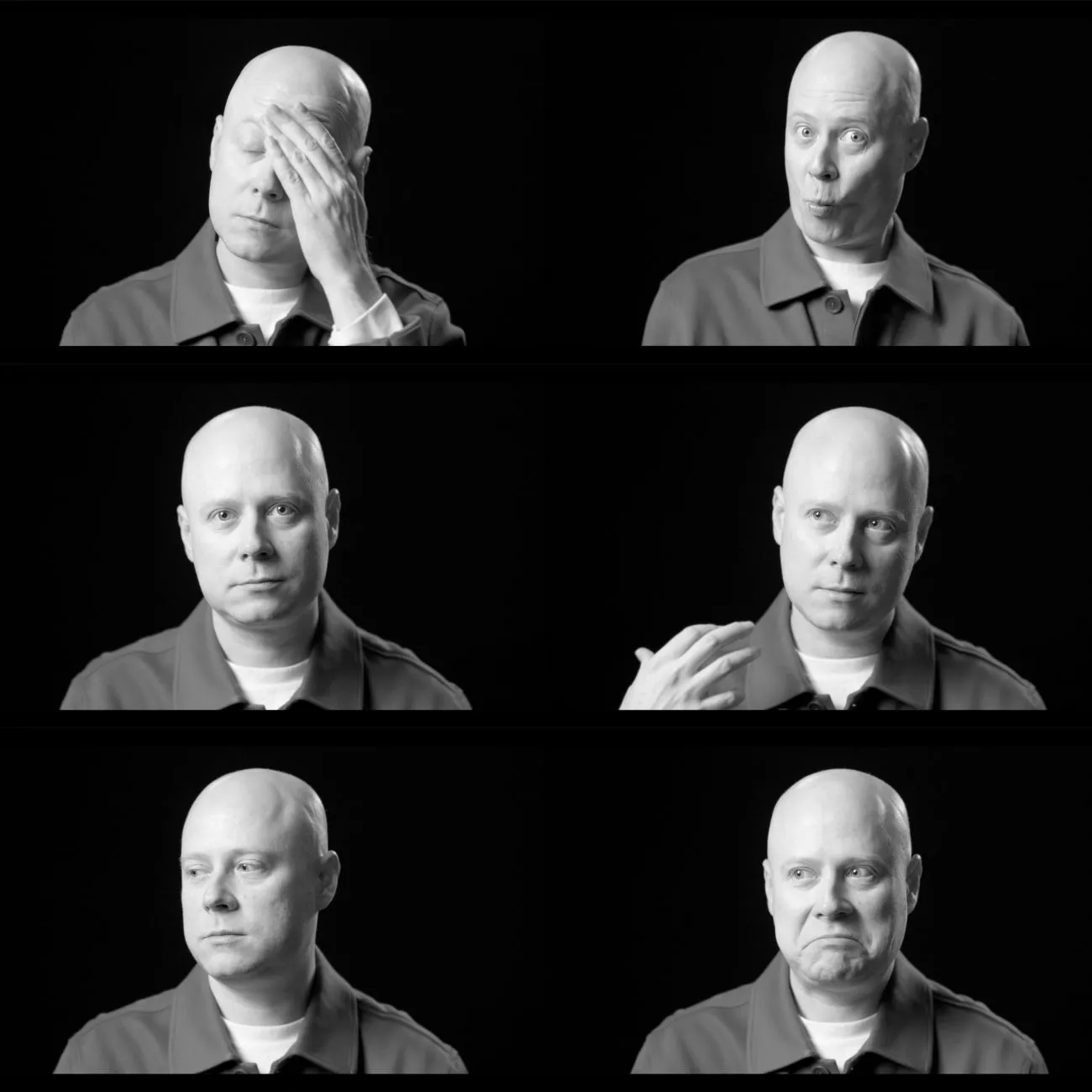

Ivan Kolpakov

Co-founder and editor-in-chief at Meduza, author of the book "We lost", editor of the book about Lenta.ru

As far back as I can remember, I’ve always been scared. I’ve met people who appeared fearless. It’s hard for me to compare the feelings. I can’t look into their heads. But it seems to me that I just have more fear than other people do. When I was 20, I found this fun and cool: facing your fears, overcoming them, I was sure if you passed a certain point then some sort of happiness would come, or some sort of Zen. It never comes, though. Either you’re happy with the fear, or you’ll just never be happy at all. Recently I had the thought that fear isn’t all that bad. It helps you stay vigilant, it helps you get through dangerous situations carefully. I no longer hate myself for being afraid. My fear has probably helped both me and the organization I work for survive.

I can’t do anything to help the people who work with us from inside Russia. I can find them a lawyer, but these days that amounts to palliative legal care. A lawyer ensures there’s no completely arbitrary abuse of power, that you don’t get beaten in pre-trial detention. I’ve learned to live with fear for my colleagues: at the end of the day, they’re journalists and they understand what could happen to them. The situation that’s much harder to bear is that of our loved ones in Russia, who are at serious risk even though they have nothing to do with journalism.

In search of answers, I acquainted myself with the experiences of people involved in activism and political struggle. Their situation is much more brutal, and it practically always puts their loved ones at high risk. Therefore, I think, it’s especially important for those people to live with integrity. You have to choose your path, your own personal belief. Otherwise you just won’t be anything — it won’t ease your loved ones’ burdens if you betray yourself. It does seem impossible to do this job if you don’t have 100% faith in your work. But I’m the biggest skeptic of journalism that you can imagine. I doubt all the time that it’s a necessity.

This explanation lets you convince yourself that there really is no choice — or if there is, that it’s the right choice. But it’s a crappy explanation, it doesn’t relieve the guilt. I have no answer for how to dig yourself out of that guilt. I don’t think you can, that’s just the price of our work.

I understand, for example, how much harm journalism does, alongside the good. And I understand how frequently we don’t do our work well enough. We don’t try hard enough, we don’t tell important stories precisely enough. Sometimes, after publication, a subject’s life changes irreversibly. It’s not always possible to know whether you’ve done everything correctly. The most unfortunate thing is when you realize: no, not everything.

I envy people who can say: "I do my work because I believe in journalism. Adults should have the full breadth of information so they can make an informed choice". I don’t think that people read the news in order to make an informed choice. It’s more like one among many types of entertainment. For us it’s not, for them it is.

The sense of life’s clarity, of relief from this existential complexity, is the sole reason that we continue this kind of work. Life is much simpler when you face a mortal threat. Under those circumstances, you have something like an innate survival instinct. You mobilize yourself and everything becomes black-and-white, very simple. Many people like this state, because it helps them disconnect from real life. Real life is much more complicated than survival situations. I think that many working journalists, activists, and people in other dangerous professions do it because it’s simpler than living a normal, complicated life.

In 2021, when Meduza was declared a "foreign agent" in Russia, we told our colleagues, "Guys, it’s been fun, but it’s impossible to continue". It was no longer possible to do journalism in Russia, it became a banned profession. It was very easy to figure out what would happen next. The only thing left was life after death. The doors you used to kick open would now have a hundred locks on them. Your employees would be persecuted. I didn’t want to be part of that. But we didn’t close Meduza, because the team wasn’t ready to close. And neither was management.

In 2022, when the world fell apart around us, I realized that we were really needed here and now. That was the most important year in my professional life: 2022. If we’d believed 2021’s "safe" calculations, we wouldn’t have done the rescue work in 2022 that helped prevent us from collapsing inward alongside Russia and the rest of the world. Of course, after 2022 everything changed. We’re another kind of publication — no longer for the wider public, but for people who are highly motivated to read the news.

Professionally and on a human level, I’m still most interested in those who find themselves in isolation, those who are locked away in an authoritarian situation and know it. These people are becoming less and less visible. But our work instructs us to notice the people who have wound up in the most vulnerable positions.

This, in fact, is the reason that I love journalism: one of the profession’s greatest ideas is to pay attention to those who have no voice, who feel themselves to be outsiders. It’s true that journalism usually focuses on specific problems, social ills. But it seems to me that sometimes the problem is that a person is simply different. He has some kind of different idea about himself and the world. In the end, you understand that you yourself are like that, different, that in helping such people you’re doing the same thing for yourself.

Ivan Kolpakov