Art born from loneliness

Alexander Gronsky, "Moscow 2022–"

Photographs, slideshow. 2022 – present

— Your project, “Moscow 2022–” has been ongoing for three years. What does your work day look like?

— I always feel like I need to justify myself with this project because it doesn’t have any kind of conceptual script — it just came together on its own. I walk around and bear witness, like a Google Street View car. A perfect day is when I wake up, eat breakfast, and wander around until it starts getting dark. I mostly go on foot, but recently I’ve started intentionally driving out to somewhere I’ve definitely never been before because I got tired of always combing over the same neighborhoods.

Alexander Gronsky

Alexander Gronsky

Alexander Gronsky

— Where do you mainly go in Moscow?

— I’m generally accustomed to moving along the edges of its territory: wooded parks, residential areas, the boundaries of the city as such. But in recent years, that’s no longer been my priority and I’m primarily attracted to spaces filled with signs — billboards, inscriptions and so on.

— Your project’s most recognizable motif is digital billboards with propagandistic content. How do you manage to capture such eloquent scenes from those videos? Do you stand in front of the screen and wait?

— Sometimes it takes preparation in advance: for example, when I know that Putin is addressing the Federal Assembly and that his speech will be shown on a digital billboard. Sometimes it’s just luck. Combining text (especially if it’s ideologically charged) and landscape is a tradition of unofficial Soviet art, like the work of painter Erik Bulatov.

— Are you consciously referencing this tradition?

— No, it’s not intentional. But I’m glad that such echoes arise. In Russia, when a text appears in urban space, we understand that it’s censored, that it’s undergone some kind of approval. It turns out that these texts are united by a common narrative of power. That really is reminiscent of the late USSR when any text that appeared in public looked like a set of letters, ritualistic phrases or incantations. Since all of these words are totally incompatible with the urban landscape, it’s as if their meaning slips off of them. On the street, the text starts to behave unpredictably — sometimes it can, for example, acquire a meaning that’s the opposite of its original meaning. It’s possible that this is the project’s central theme.

Alexander Gronsky has been called the first Russian representative of deadpan — the deliberately "boring", detached, dispassionate photography associated with the Dusseldorf School. Gronsky’s main genre is landscape; the typical environments of his photographs are the Moscow outskirts, wooded parks and residential areas built up with identical high-rise buildings. In one of his early projects, "Pastoral", views of Moscow recalled classical landscape painting and, by association, seemed to become more attractive. The photographer showed that we see "beauty" where cultural habit tells us to.

Another important theme in Gronsky’s work, closely connected with the problematics of photography in general, deals with counterfeits, fakes and imitations. He has shot, for example, battle reenactments and architecture that mimics his-torical forms. "Moscow 2022–," the project Gronsky has been working on since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, unites both motifs. He photographs the big city that tries not to notice the war, but inevitably changes under its influence.

Alexander Gronsky was born in Tallinn in 1980. At the end of the 1990s, he began working as a photojournalist, and at the end of the 2010s as an art photographer. He has won numerous prestigious awards, including the World Press Photo, the Foam Paul Huf Award, and the Russian "Innovation" Prize. His solo exhibitions have been shown in Paris, London, New York, Amsterdam, Tokyo, and other cities. The photographer’s works are held by Amsterdam’s Foam Museum, New York’s Aperture Foundation, and Paris’ Maison Européenne de la Photographie. Gronsky lives and works in Moscow.

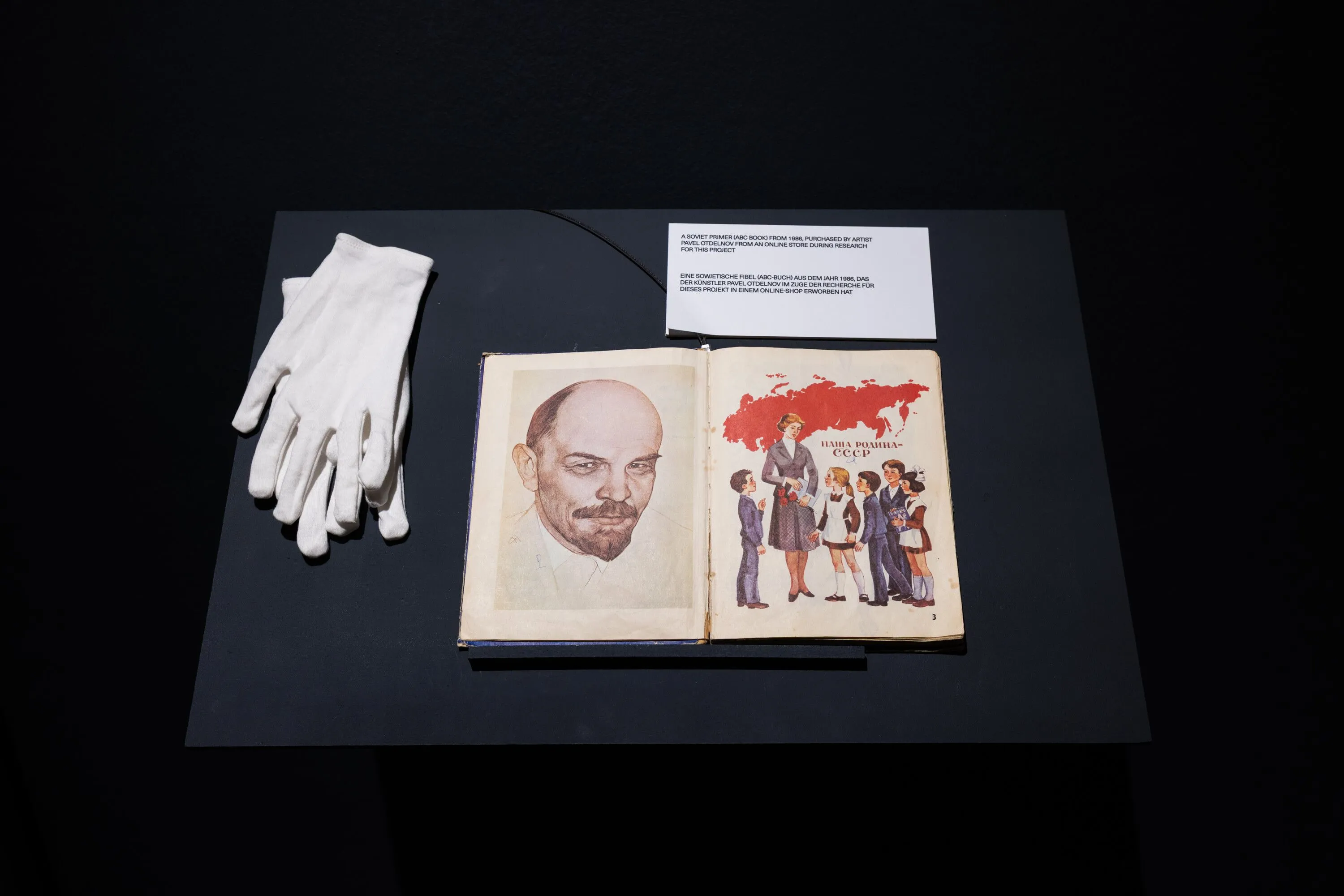

Pavel Otdelnov, "Primer"

Canvas, acrylic, 2024

— Is your “Primer” series connected, in your mind, to the concept of loneliness?

— On the contrary, "Primer”" might be described as the collective hallucinations of my generation. My project is about finding common ground — that includes people with diametrically different positions. Regardless, we were all educated in the same Soviet system, with the same basic configurations and ideas about the world. In the "Primer" series, I plumb the depths of my childhood memories in pursuit of those configurations. Instead of using pictures from a real school alphabet primer, I capture the words and images that were truly formative for me and many other people of my generation.

The letter Я — pit (ямa/yama) is about the fear of death, the awareness of mortality that came to us in childhood. T is for television (тeлeвизop), an object that structured Soviet family life: sometimes the kids watched it, at other times the adults did. B is for the abyss (бeзднa/bezdna), the image of catastrophe that is connected with my country, with Russia. S is for toy soldiers (coлдaтики/soldatiki): war was the main game of the sandbox — no one wondered why these soldiers were fighting. A is for toy soldiers again, shouting "Au! Hoorah!" (Ay! УУpa!). When I was a kid it seemed that "hoorah" always brought everyone together. I never expected that I’d hear a kind of "hoorah" I’d want nothing to do with.

R is for radiation (paдиaция), something frightening and invisible, that might be anywhere. Z is for winter (зимa/zima) — nuclear, it stands to reason. U is for shelter (убeжищe/ubezhishche), another concept associated with childhood fear. In elementary school, Konstantin Lopushansky’s film "Dead Man’s Letters" made a very strong impression on me. In the movie, there’s a nuclear winter after an atomic war, and all these people lose their minds and die in dark shelters. I decided that if there was a nuclear war, I wouldn’t go into any shelter, in fact I’d go out on the street specifically to die a quick death, rather than dying from hunger and suffocation. When I told my classmates this, one of them told on me and my parents were called into school. L is for Lenin, the chief deity. From today’s perspective, these ubiquitous portraits of Lenin strike me as a justification of terror for the sake of great ideas.

The letter combinations Mya, Rya, Vya, Sya, Pya, Tya, Nya (мя, ря, вя, ся, пя, тя, ня) are taken from a real primer. It’s practically avant-garde poetry, almost like “Dyr bul shchyl” by Alexey Kruchenykh. They sound as though someone is trying to start talking about something unpleasant, something people try to ignore. Of course I was thinking of war: in my childhood, when the war with Afghanistan was going on, it was also a repressed topic, like it is in Russia today.

— It’s hard not to see echoes here of the Moscow conceptualists and conceptualism in general. Is this analogy meaningful to you?

— It’s always important to me, not just in this series. The work of Moscow conceptualism is built on the idea of a break, a gap between word and image, where something unspoken fits in. I’ve worked with this before, for example, in my "Industrial Zone" series I painted the ruins of factories alongside quotes from a book of my dad’s, who worked his whole life in Dzerzhinsk chemical plants. My dad’s memoirs, which I display in the exhibition, and the cold ruins in my pictures not only don’t illustrate each other; they almost negate each other.

Apart from Moscow conceptualism, some of my work references Ed Ruscha, an American artist who worked with words on landscape. In his work, the word itself turned into landscape and shaped it. But where Ruscha works from a world of endless advertising slogans that have shaped the U.S. space, like the Hollywood sign, I use the words and meanings that define the habitat I’m accustomed to.

Pavel Otdelnov works in painting, graphic arts, installation, photography, and video. His main genre is landscape. Otdelnov paints industrial parks, residential areas, landfills and other uninviting spaces. He produces figurative art, but at the same time many of his works, like the "Neon Landscape" series with blurred city lights, are reminiscent of abstract painting.

Otdelnov was born in 1979 in Dzerzhinsk, in the Nizhny Novgorod region — a city kept alive by the chemical and defense industries. His childhood in Dzerzhinsk defined his sphere of interests: the fate of Soviet ideology, daily life in industrial regions, militarism and state violence.

The artist unites his works in conceptual cycles, which he exhibits in a particular fashion. The "Ringing Trace" project, for example, was essentially a total installation in an abandoned constructivist dormitory in Snezhinsk. It portrayed the Kyshtym radiation disaster through painting as well as texts and found objects.

Otdelnov studied in Moscow, where he graduated from the Surikov State Academic Institute of Fine Arts and the Institute of Contemporary Art. He has participated in the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art and the Ural Industrial Biennale. In 2020, Otdelnov won the Innovation Prize and the Moscow International Market for Contemporary Art Cosmoscow named him Artist of the Year. He has lived and worked in London since 2022.