Art against war

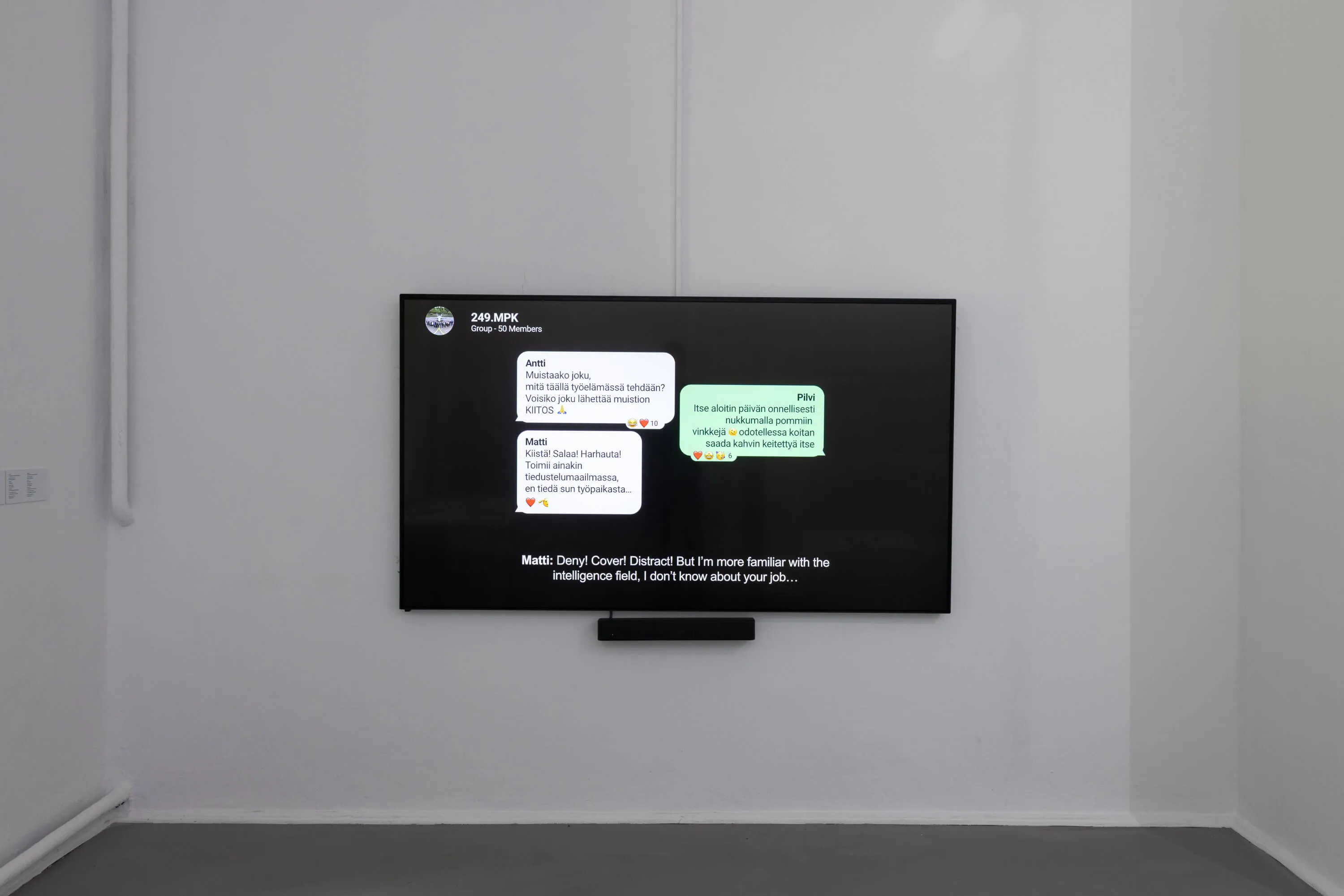

Pilvi Takala "Feeling Defensive"

Voices: Pilvi Takala and Johanna Vuorelma

Camera: Katharina Diessner

Sound editing: Pinja Mustajoki

Production assistants: Tuure Leppänen, Iona Roisin

Research assistant: Jessie Bullivant

Pilvi Takala

— In your project you describe the training you received from the military. What was it?

— I attended this thing called the "National Defense Course", which the Finnish Defense Forces (the Finnish military) have been organizing since the 1960s. It’s almost four weeks long and the idea is to invite a group of participants who are prominent in their fields — such as members of parliament, government administrators, and CEOs, along with others from the defense forces, the business world, the media, academia, the cultural sphere, and various NGOs — to come together and learn about defense and crisis preparedness. Attendees participate in lectures, field trips, and roleplay exercises where they practice decision making in a national crisis scenario.

There’s a kind of mythology surrounding the course, people are very proud to be invited, and their employees are proud of them as well, paying them a full salary while they attend.

— What did you make of it?

— Well, I was very much outside my comfort zone thr

oughout the course. The recurring use of language like "fatherland" and the assumption of a shared patriotism felt wrong to me.

As a Finn, I have a lot of trust in the systems in place, and the course does manage to foster a commitment to working together in times of crisis. However, the defense forces were really overrepresented as the main safety organization, and so war was the main crisis scenario (instead of climate change, for example). The discourse was so one-sided that it was hard to challenge, even though some of us tried to ask critical questions. There was barely any talk about deescalation, peacebuilding, or international law. As much as I wanted to challenge the narrative, it’s extremely hard to carve out space for critical conversation because the course isn’t designed that way — it’s designed to integrate you into their system. Participation included posing next to tanks for group photos and being in uniform during our three-day stay at a military base, which ultimately felt like consenting to their agenda.

In my research, I pay attention to how this course is engineered to pull people in, looking at what worked on me and what didn’t. I’m also interested in my role as an artist in this course. Someone in the course asked a great question: how can we make artists create patriotic art in times of crisis if they’re all liberals and will just critique everything? I feel that my job as an artist is to deal with things that are difficult, complicated, or contain some kind of tension. I don’t think that role will change in times of crisis — it might actually become even more important.

— Is it usual for people in Finland to talk about the threat of war in their everyday lives? Or is it something that’s started to happen more in the past three years because of the Russo-Ukrainian war?

— More than half of the Finnish population have been involved in the military in some capacity: we have compulsory military service for men and voluntary sup-plementary training. People are primed to consider war with Russia as a very real possibility and are expected to be ready.

Even with all of that in the background, you can see how the reality of Russia invading Ukraine has totally shifted the public discourse. Finland immediately joined NATO and the move was largely uncontested. A society that was already pretty militarized has become even more so.

The national defense budget has snowballed too. Of course they will never say "hey, that’s enough money, we have everything we need now" because there is an unknown threat, so all eventualities have to be prepared for and you can never be 100 percent prepared. There is no end to this logic and it is hard to counter — the discourse around threat erases everything else.

Pilvi Takala’s video works are based on performative interventions in which she researches specific communities and institutions to question social structures. In her practice she shows that implicit normative rules for behaviour are often only revealed through disruption. For example, in "Bag Lady", Takala walked around a shopping mall with a large amount of cash in a transparent bag: Staff became uncomfortable and visitors who were worried about the safety of the money persuaded the artist to hide it. For the project "Real Snow White", the artist tried to enter Disneyland dressed as Snow White: Employees refused to let her in, arguing that she was not employed by the theme park and therefore did not answer to the company, but might do "something bad" in the character’s image. Takala’s performance called attention to the absurd logic of appealing to Snow White’s "real character" as well as Disneyland’s extreme discipline.

Sometimes Takala works more explicitly with groups. In "The Committee", a work created by the artist after winning the Emdash Award, she invited children aged eight to twelve to come up with ideas for how to spend £7,000 of the prize money (the children spent it on a bouncy castle). Another example is a recent performance called "Close Watch". Takala worked for six months as a security guard at a shopping center, after which she invited her former colleagues to take part in a participatory theater workshop to reenact difficult work situations with the help of professional actors.

Pilvi Takala was born in Helsinki in 1981. She represented Finland at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022. Her work has been shown at Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich, Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, CCA Glasgow, Manifesta 11, Centre Pompidou, MoMA PS1, Palais de Tokyo, New Museum in New York, Kunsthalle Basel, Kunstinstituut Melly, and the 9th Istanbul Biennial. Takala lives and works in Helsinki and Berlin.

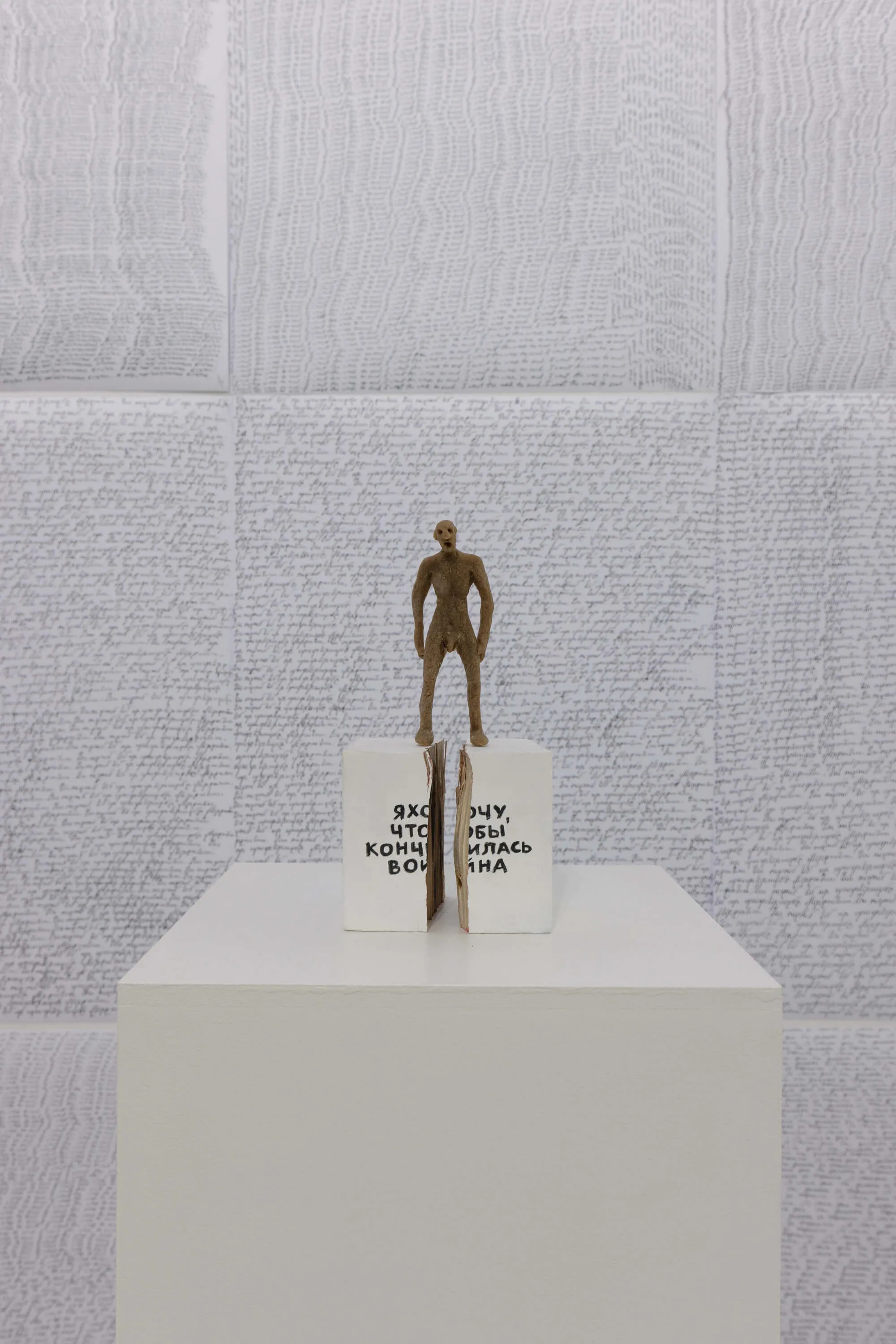

Anonymous artist "Time of War"

Performative graphic. Paper, ballpoint pen. 65 × 50 cm, 150 sheets. 2022–2024

— What’s your working process for the “Time of War” series?

— The series right now consists of 150 sheets of paper, covered in small inscriptions in ballpoint pen. The words "I want the war to end" are all over them in different languages.

I started this series on December 16, 2022, after I was forced to emigrate to France. It was in large part psychotherapy, the sublimation of a naive, childish desire, which millions of people across the political spectrum share with me.

I worked on it actively for around a year; sometimes I even did several pages a day. I always write in Russian, Ukrainian, and English — and I add the language spoken wherever I’m staying. Usually that’s French, since France is my main location. But you can also see Armenian, Hebrew, German, Dutch, and Czech. Essentially, this is a visualization of time, filled with a single strong desire — an end to the killing.

I’ll consider the series over when the war is over. One way or another, it’s a work in progress. I’m working on it much less now than I was during the first year of the war. Initially I thought I could influence the situation in some mystical way. But it went in the opposite direction: yet another war broke out, and that couldn’t help but dampen my energy for the work.

— You call this series performative graphics. What is that?

— What’s important isn’t only the result, but the process itself. The process might even be more important than the way it looks. I didn’t make any special graphics,

I didn’t choose a font, everything happened spontaneously.

— You write, “I want the war to end”, not “I want people to stop fighting”. As though it’s a natural phenomenon.

— I know that Russia is responsible for the war. War begins by the will of people. But I’m not sure that it’s possible to end it by force of will. It’s like a plague. I have a feeling of powerlessness, senselessness — only the desire for all of it to stop.

The artist has chosen to stay anonymous due to security reasons.

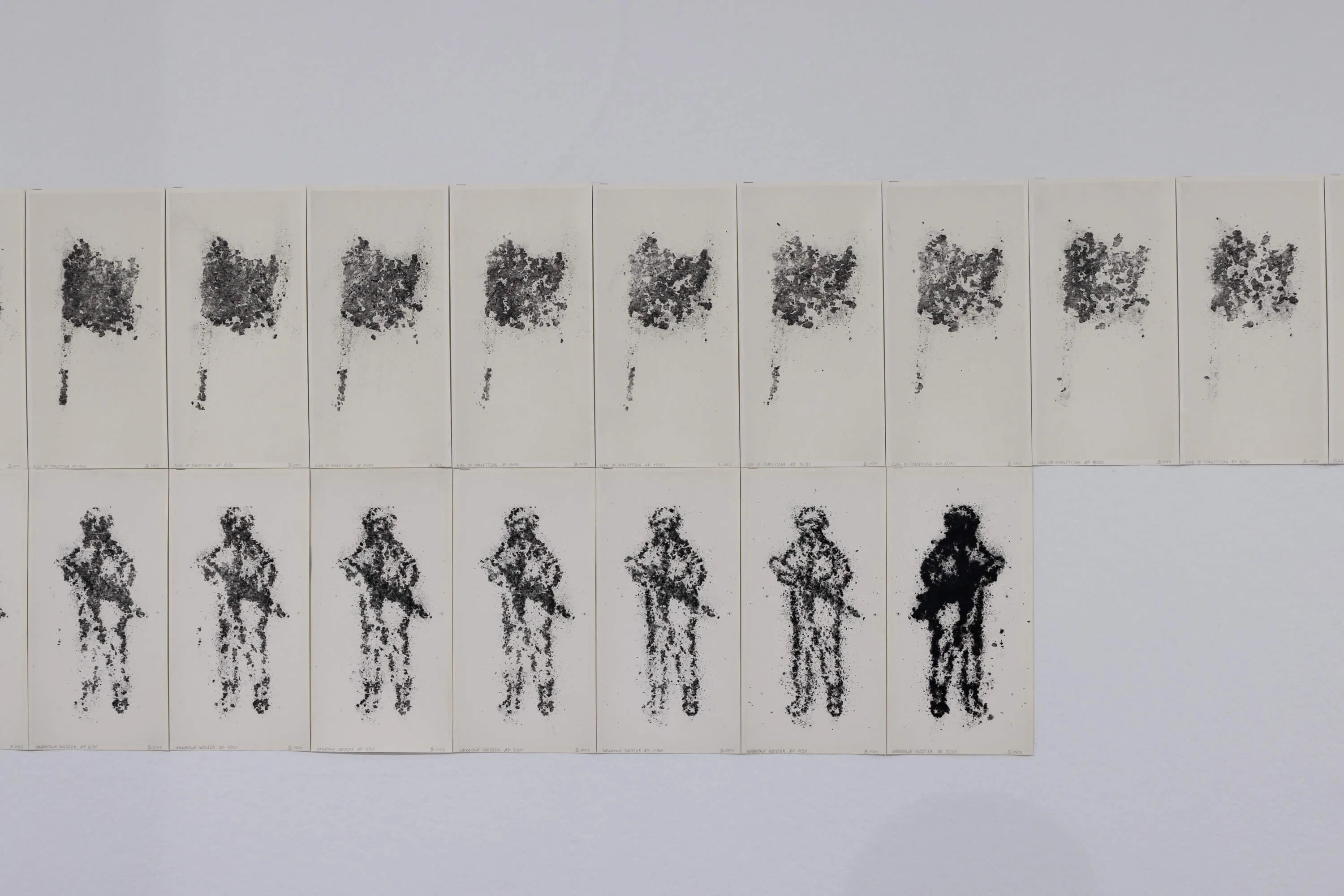

Sergei Prokofiev "Hell"

Mixed media, 2015–the present

— You’ve been working on the project “Hell” since 2015, almost since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war. Describe the project’s history.

— The killing of [Russian opposition politician and reformer] Boris Nemtsov [in 2015] was a turning point for me. I realized that I could no longer continue making light installations. I became aware of photos and videos coming from the Donetsk airport, which at that time was a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. The texture of the destroyed airport, especially the new glass and steel terminal, matched the texture of the models I had been trying to make with a 3D pen: skeletal, burnt-out looking black structures. I realized that I needed to record this because the news has a tendency to fade into oblivion.

There was a lot of joy at that time in Russia, a morbid enthusiasm for the annexation of Crimea. There were a few sporadic art pieces that reflected on the situation, but I didn’t see any artistic commentary about the war in the form of a large exhibition project — so I decided that it needed to be done.

When the full-scale invasion began, I reactivated this project. After a few months, my psyche activated a defense mechanism that pushed me away from unfolding events. That’s why symbols connected to nature absorbing and processing traces of war started to permeate my work. Symbols related to memory also appeared. In the summer of 2023, I started burning sculptures, extracting graphite out of them, and using it to print a series of 30 sheets of paper: every print was fainter than the previous one. These series are very much about working with memory.

— Many anti-war artists today are forced to ask questions like “Why do we need art in times of war?” or “Can art make sense of events that are happening right now?” How do you answer these questions for yourself?

— I asked myself all of these questions in the spring of 2022. Not long before the full-scale invasion, I had been planning to go knocking on the doors of all Russian art institutions with my anti-war project: "Nothing is over, the war continues in a smoldering phase, we need to show it". In the end, life turned out differently. I realized that I needed to continue this work in the conditions and with the resources available to me. Can you make art in a time of war? I think you can and you must, you must do it here and now, even though nothing has cooled down yet. It needs to be recorded in physical form instead of getting lost in the ever-flowing media stream.

It is a practice of witnessing — and in my case it’s meditative and actually quite archaic. Art works made with a 3D pen and graphite plastic, for example, look old, often resembling fossilized traces of plants and animals despite the fact that the technology itself is new. The scars of trenches cutting through farmland and fields in my last series of reliefs are reminiscent of geoglyphs from Chile. These archaic motifs are connected, for me, with the archaic nature of war itself.

Sergei Prokofiev creates sculpture, graphic art, video, and light installations. One of the artist’s favorite techniques is a three dimensional linear drawing that unites features of sculpture and graphics. In the early 2010s, he "drew" with fluorescent lamps, producing objects in the spirit of classical minimalist Dan Flavin, before switching to a 3D pen.

Prokofiev’s works often make reference to political reality, as, for example, with his early pieces "Block" and "Smart Bomb", which were a police barrier and a guided aerial bomb made of fluorescent lamps. Both pieces stem from the beginning of the 2010s, a period when many in Russia lost hope in swift democratization. The lamps contain toxic mercury vapor: the artist chose this material intentionally to depict symbols of power and the violence that it exerts.

Prokofiev has continued developing the same theme for over a decade as part of his "Hell" project on the Russia-Ukraine war. The series, which includes objects, graphics, and videos, began with an architectural model made with a 3D pen. It depicted the Donetsk airport destroyed by fighting, a place emblematic of the first phase of the war, during which Russia partially occupied the Donbas region (the airport, which now lies in ruins, bears the name of the Russian and Soviet composer Sergei Prokofiev, the artist’s full namesake).

Prokofiev himself says that art for him is a form of resistance, not only to the outside world, but also against himself. He believes that this resistance is only possible because of a fundamental disagreement — with himself and the existing order of things.

Sergei Prokofiev was born in Moscow in 1983. In 2013, he graduated from Moscow’s Joseph Backstein Institute of Contemporary Art. Two years prior, in 2011, Prokofiev founded, alongside Andrei Mitenyov and Lyokha Garikovich, the art space “This is not here.” In 2016, the artist joined the team at the Elektrozavod gallery. Prokofiev has had solo exhibitions in Russia, Italy, Sweden, Denmark, and France. He participated in the parallel program at the Manifesta Biennial in St. Petersburg, and in the Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art. Prokofiev’s works are held by the Tretyakov Gallery and in the Luciano Benetton collection. He lives and works in Paris.

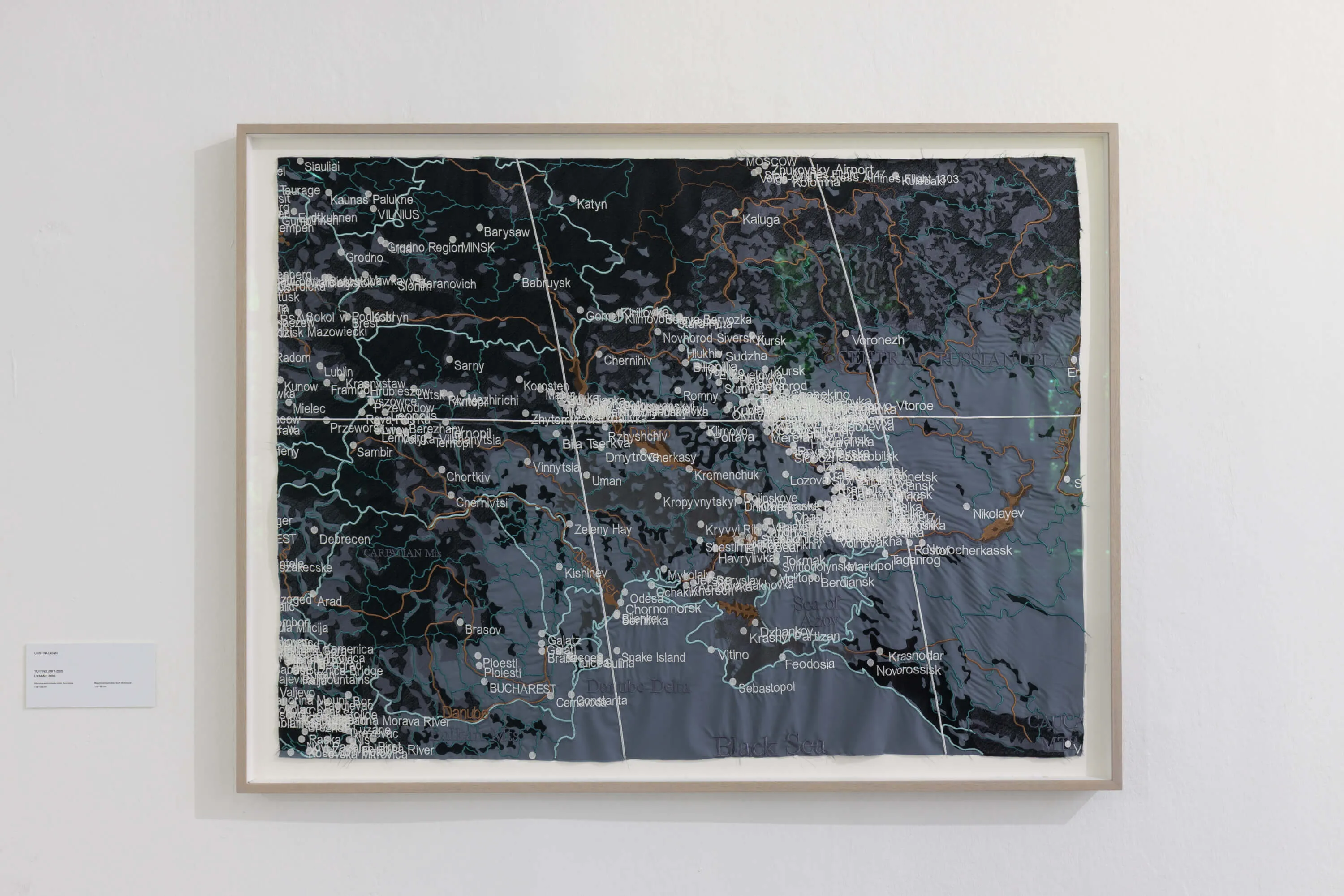

Cristina Lucas,"Tufting"//"Ukraine 2025"

Machine-embroidered cloth, 2017 — present

— What’s the story behind the project?

— This work is deeply connected with Picasso’s "Guernica". Now in Spain, we are revisiting the memories of the Spanish Civil War. Once the dictator [Francisco Franco] died, all the democracy was based on a silent agreement. It seems a kind of sickness when you are unable to talk about your traumas. Recently, in the 21st century, some artists are working with the memory of the Civil War because there are a lot of Spanish victims from the Republican side still in the ground without being identified and without the families being able to lay them to rest. So it’s a kind of healing process to talk about it again.

For the 75th anniversary of Picasso’s painting, I was asked to make a commission about Guernica as a concept. I was not very much focused on the painting itself, but I was thinking about all the aerial bombing in the Spanish Civil War, which was a kind of rehearsal for World War II. I decided to make a compilation of all the aerial bombing of civilians from both sides, keeping in mind that the tragedy of the civilians is not a question of politics, it’s a question of terror.

I decided to start searching for all the aerial bombing of civilians since it has been possible to fly, because flight was an old dream of humanity which suddenly turned into a nightmare. You can see all the data moving on three screens — and the embroideries are kind of a summary of all that information. So this is what we are going to show in the new exhibition, paying attention to what is going on today in Ukraine.

— Why did you choose embroidery?

— I was thinking it could be a print. But then I imagined the land as a kind of a fabric which is also made out of a lot of connections. An embroidery on an area that was heavily bombed is more emotional because it looks like a scar on the fabric.

— Textile art is having a kind of a renaissance nowadays. Why do you think that is?

— Maybe it’s because this technique is connected with femininity. The people working on the database search in our project were mostly women. I should say, you need a huge amount of patience to collect all this data — this work feels much like embroidery.

Cristina Lucas works with data — whether it be the prices of chemical elements, global trade routes, or the slang names for genitalia in different cultures — in many of her projects. Although the language of art and the language of science are traditionally considered distinct from one another, the artist demonstrates that data can both help us understand reality and be used as an image. In the installation "Clockwise", for example, Lucas hung 360 clocks around the perimeter of a circular room, showing all possible times on a globalized planet simultaneously. The chorus of out-of-sync clocks was reminiscent of the sound of rain.

The artist creates videos, installations, sculptures, and photographs. Her main themes are human rights, with a particular focus on women’s, capitalism, and war — in a word, power. One of Lucas’ favorite media is the geographical map, often dynamic, on which the viewer can follow certain events, such as the military expansion of states or the spread of democracy.

Cristina Lucas was born in Úbeda, Spain, in 1973. She studied at the Complutense University of Madrid, the University of California, Irvine, and the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. The artist has participated in the Manifesta Biennial in Palermo, and the Liverpool and Ural Industrial Biennials, among others, and has had solo exhibitions in Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, Luxembourg, and Mexico. Lucas’s work has been acquired for the collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Kiasma Museum in Helsinki, and many other institutions. She lives and works in Madrid.